Consciousness and the Nature of Thought

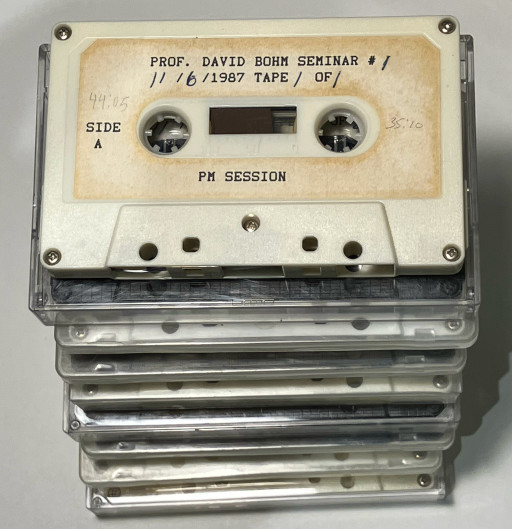

• 1987 November 6-8 [9]

• 1988 November 11-13 [10]

• 1988 December 2-4 [9]

• 1989 November 3-5 [9]

• 1989 December 1-3 [9]

• 1990 November 2-4 [9]

• 1990 Nov 30 - Dec 1-2

• 1992 March 20-22 [9]

p.17

We raised the notion that thought is based on memory. That’s an interesting point, which may be a clue. I want to distinguish between thinking and thought. I say ‘thinking’ is an active process which is actually going on. The syllable ‘ing’ suggests something active. And ‘thought’ is the past.

We suppose that we think, and that the thinking then vanishes. It is assumed that thinking tells you what is right – the way things really are. Then you decide what to do, and you do it. And then it’s all gone. But in fact, I say thinking doesn’t vanish. It becomes thought, and it goes onto a program. What you have been thinking goes onto a program – especially the conclusions and the assumptions and the general things like that....

p.19

We’re saying you have thinking and thought. Thinking is a bit more active, because when you are thinking you can sometimes detect incoherence – you can detect there is something wrong with what you are thinking. But thought acts like a program, and works so fast you can’t do that. Then how do you detect incoherence? You get a feeling – a sense something is wrong. And you require sensitivity to that.

That sensitivity is crucial. We won’t have time to go into it this evening, but I think society systematically destroys sensitivity in order to avoid being upset. It would rather people not notice incoherence, because then they don’t upset the apple cart too much. Therefore, we have learned to cover it up.

Let’s say that we have this sensitivity which is very subtle, which can show us incoherence in our thought and action. It can show us that we say one thing and do another, and so forth. But usually we don’t want to be sensitive to that.

We have thinking and thought. Besides that, we have feeling or emotion – whatever you want to call it. Now, feeling has the suffix ‘ing’, which suggests something that is always active and primary and real. But that’s not true. Unfortunately, the English language is deficient in this regard. It has introduced the distinction of thinking and thought, but it has not made a corresponding distinction among feelings. I will do it for the moment now.

I say there are feelings and ‘felts’. Feelings you had in the past have gone into the memory and become programs. You can remember feelings you have had – feelings of traumatic events, feelings of pleasure, nostalgia, and so on. That has a powerful effect. You find it hard to distinguish them from some genuine feeling....

pp.26-27

If you don’t like what the other side is doing – say the communists or the capitalists, or in religion – you form an image of them as wicked and you say, “They are always that way. They only understand force.” That’s typical of what people frequently say. Of course, nobody ‘understands’ force. If somebody responds to you with force, it will create the sense that you have been violently treated. Also, if people don’t listen to you, you will feel that is a form of violence. In both cases, you may think that a violent response is what is called for.

It is a complex problem, because you may see somebody else’s violence and say that it is his violence. But it is really yours as well, because you cannot see his violence except in terms of your own – your own tendency to use undue force inwardly or outwardly.

Suppose you are watching a television program with a violent content. There is nothing going on there at all except spots of light, but you can feel the violence in the program. Where is it actually coming from? It is coming from your own violence.

Each person has been programmed to violence over the ages. And everybody has plenty of violent programs in him. There is no difficulty in finding a violent program to project into the television image, or to project into the memory image of somebody else. The point is that if you see violence, you see it through your own. Then you think, “That’s terrible. It’s disturbing.” So you deny that it is yours and say, “It’s that person’s,” and you feel better. But the violent movement involving undue use of force is still in there, and will come out in another way in distorting your thought.

As I’ve already said, we may also have a thought which says that I am justified in responding to violence with violence. I respond to friendship with friendship and to violence with violence. That is a commonly accepted thought. But that thought cannot actually work overall in the long run. It must lead to sure destruction. It destroys all sides, because once you respond with violence you are turning your own system into chaos, and everything you do goes wrong – has no meaning.

This is a very subtle point. It requires a lot of sensitivity to see it. But of course, violence is constantly destroying that sensitivity. Your violent reaction is smashing you up inside so that you are not sensitive. You’re not only not sensitive to that, you are not sensitive to almost anything else, and you do all sorts of things wrong. So you could see that one of the basic difficulties with thought is violence.

The other side of violence is fear. When you think you’ve got a lot of force, you probably won’t hesitate to be violent – to use force to overcome. But when you don’t think you have that force, then you’re afraid and you try to retreat. The point is that fear and violence are closely connected – not only in the ways I’ve just described, but also because you can project your own violence onto the other person and you become afraid of it. Therefore, the two go together. They are just two sides of that one process.

You can see that physical violence is a tremendous problem, but mental violence is a much more serious problem. You can see violence in the way people insist on their view and simply dismiss anything else. That will provoke further violence.

pp.51-53

We can hold a block of concrete in our hands; that’s what is called ‘manifest’. In Latin, ‘manifest’ means literally ‘what you could hold in your hand’. But the thing that holds society together isn’t manifest. You can’t put it in your hand. The things you can put in your hand will not hold society together.

We have raised the question: what is the nature of this subtle concrete, glue, cement? I say it is the sharing of meaning. I am saying that the concrete basis of society is that meaning – whatever meaning is.

Now, meaning is not just abstract. You see, behind the abstraction is something concrete – the concrete reality of the very thought process itself – or more generally, of the overall mind process. And underlying this is meaning. In an elementary case it is thought which has a certain meaning, words which have a certain meaning; but there may be more subtle meanings.

Q: For an individual, the concrete reality is the meaning. For instance, with a table the meaning is in a sense what the table is – what it represents to him.

Bohm: Yes. And also the meaning of the whole room is what holds it all together as a room. The meaning of your life is what would hold it together. If it lacks that meaning, then you feel it is falling apart. If society lacks a common meaning, or the culture lacks it, it won’t hold.

Culture is the shared meaning. And meaning includes not only significance, but also value and purpose. According to the dictionary, these are the three meanings of the word ‘meaning’. I am saying that common significance, value, and purpose will hold the society together. If society does not share those, it is incoherent and it goes apart. And now we have a lot of subgroups in our society which don’t share meanings, and so it actually starts to fall apart.

Q: This almost sounds too mechanical – that these things can hold society together. It sounds as though they couldn’t really.

Bohm: Why not?

Q: Well, it would seem like the thing that would hold the society together wouldn’t be a ‘thing’.

Bohm: But meaning is not a thing. You can’t point to the meaning. It is very subtle.

Q: Then you say ‘shared values’?

Bohm: That is one of the aspects of meaning. If we want to say what the meaning itself is – the concrete reality of the meaning – we can’t get hold of it. But we can experience it in various forms – like the significance, the value, and the purpose. If we share meanings, then we will have a common purpose and a common value, which certainly will help hold us together. We have to go more deeply into what that means.

Q: Is the difference between significance, value, and purpose important for this discussion? And if so, could you expand on that?

Bohm: There is not a fundamental difference. They are really different aspects of the same thing. ‘Significance’ has the word ‘sign’ in it, indicating that it sort of points to something: ‘What is the significance of what we are talking about? What is the significance of what we are doing?’ That is one idea of meaning.

Value is something which is part of it. If something is very significant, you may sense it as having a high value. The word ‘value’ has a root which is interesting – the same root as ‘valor’ and ‘valiant’. It means ‘strong’. You might suppose that in early times, when people sensed something of high value they didn’t have a word for it, although it moved them strongly. Later they found a word for it and said it has high value. And then later the word itself may convey that.

If something is significant it may have a high value. And if it has a high value, you may have or you may develop a strong purpose or intention to get it, or to sustain it, or something. Things that do not have high value will not generate any very strong purpose. You would say, “It’s not interesting. It doesn’t mean much to me.”

“It means a lot to me” means it has a high value. And “I mean to do it” is the same as to say, “It’s my purpose.” You can see that the word ‘meaning’ has those three meanings. And I don’t think it is an accident; I think they are very deeply related.

↑ Seminars

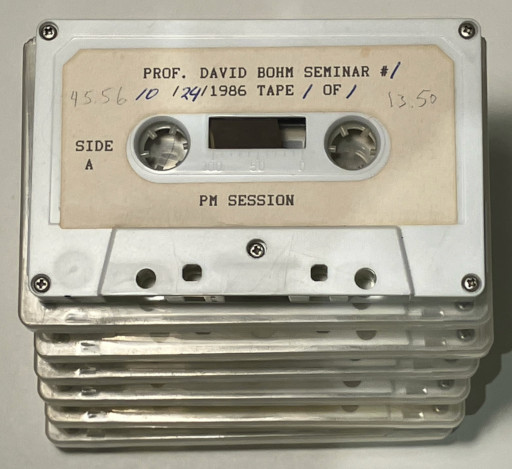

- ↑ Prof. David Bohm Seminar #2, 1986 October 24-26

-

↑

Prof. David Bohm Seminar #1, 1987 November 6-8

- Tape #1 (1:25:04) Friday Evening

- Tape #2 (0:59:25) Saturday, 10:00am

- Tape #3 (0:49:41) Saturday, 11:15am

- Tape #4 (1:09:06) Saturday, 4:00pm

- Tape #5 (0:43:35) Saturday, 5:15pm

- Tape #6 (0:58:34) Sunday, 10:00

- Tape #7 (0:41:05) Sunday, 11:30

- Tape #8 (0:59:38) Sunday, 4:00pm

- Tape #9 (1:15:40) Sunday, 5:15pm

-

↑

David Bohm Seminar #1, 1989 November 3-5

- Tape #1 (1:26:02) Friday Evening

- Tape #2 (1:06:33) Saturday, 10:00am

- Tape #3 (0:49:41) Saturday, 11:15am

- Tape #4 (1:09:06) Saturday, 4:00pm

- Tape #5 (0:43:35) Saturday, 5:15pm

- Tape #6 (0:58:34) Sunday, 10:00

- Tape #7 (0:41:05) Sunday, 11:30

- Tape #8 (0:59:38) Sunday, 4:00pm

- Tape #9 (1:15:40) Sunday, 5:15pm

-

↑

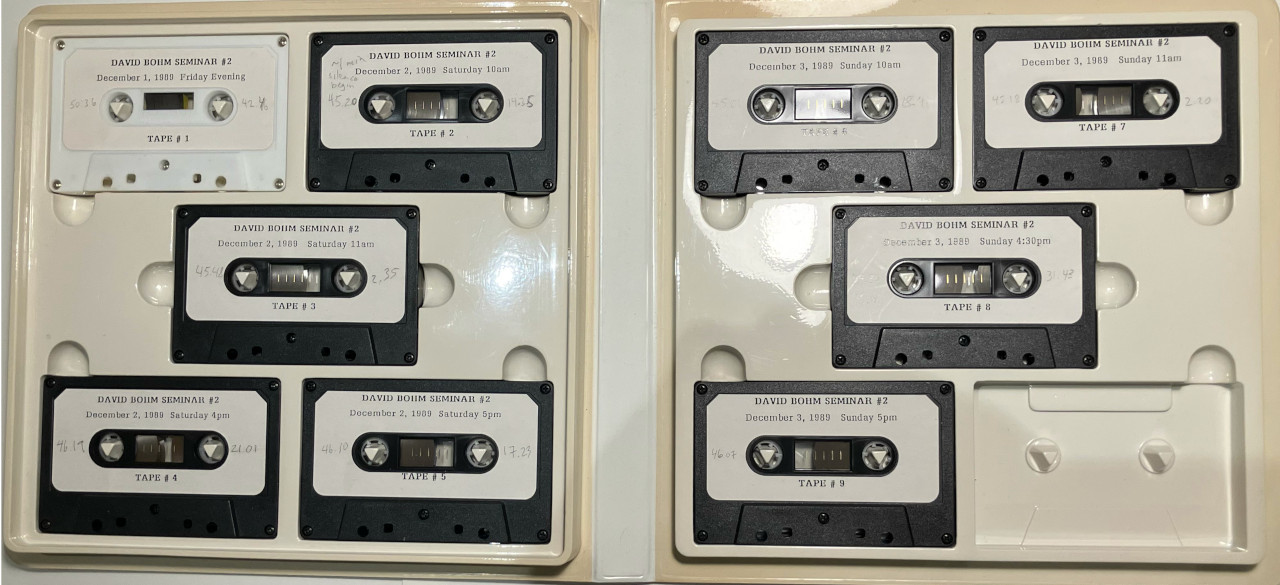

David Bohm Seminar #2, 1989 December 1-3

Proprioception Of Thought:

Transcription edited by Dr. Bohm: HTML, PDF formats.- Tape #1 (1:34:04) Friday evening - p. 1

- Tape #2 (1:00:00) Saturday, 10:00am - p. 37

- Tape #3 (0:48:44) Saturday, 11:00am - p. 58

- Tape #4 (1:07:17) Saturday, 4:00pm - p. 79

- Tape #5 (1:03:52) Saturday, 5:00pm - p. 104

- Tape #6 (1:04:03) Sunday, 10:00am - p. 133

- Tape #7 (0:47:58) Sunday, 11:00am - p. 160

- Tape #8 (1:17:08) Sunday, 4:00pm - p. 179

- Tape #9 (0:46:14) Sunday, 5:00pm - p. 210

- INDEX

- ↑ David Bohm Seminar, 1990 Nov 30 - Dec 1-2

-

↑

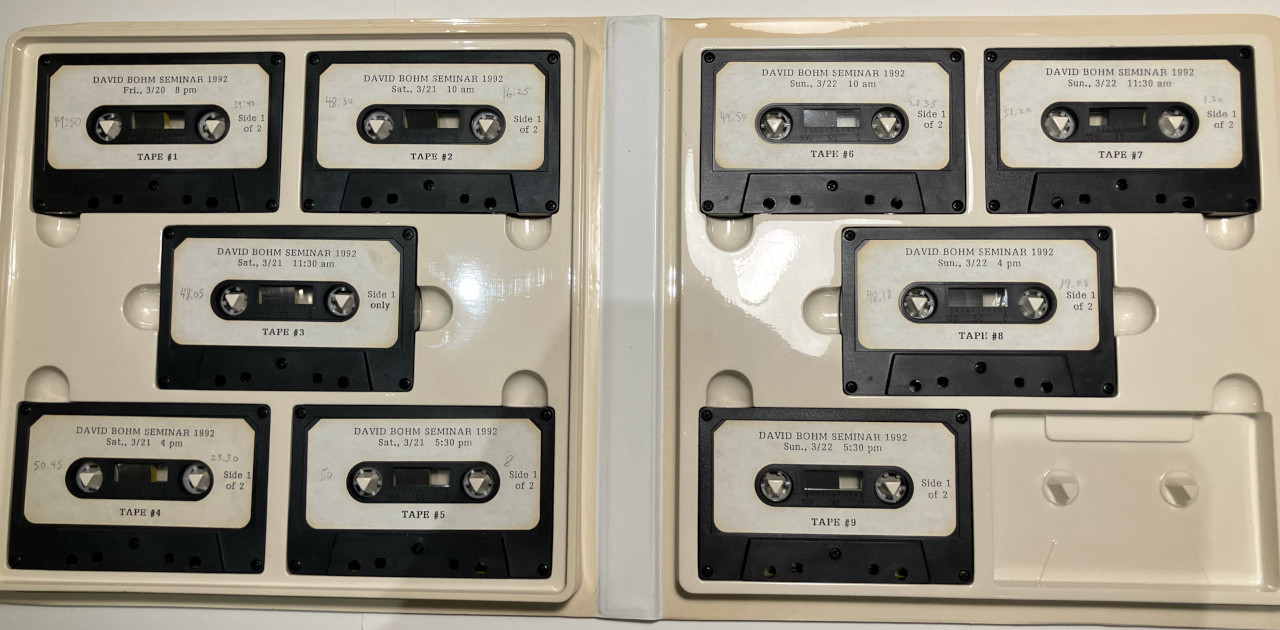

David Bohm Seminar, 1992 March 20-22

- Tape #1 (1:29:34) Friday Evening

- Tape #2 (1:06:41) Saturday, 10:00am

- Tape #3 (0:47:26) Saturday, 11:30am

- Tape #4 (1:13:33) Saturday, 4:00pm

- Tape #5 (0:57:39) Saturday, 5:30pm

- Tape #6 (1:16:33) Sunday, 10:00am

- Tape #7 (0:51:54) Sunday, 11:30am

- Tape #8 (1:09:50) Sunday, 4:00pm

- Tape #9 (1:15:31) Sunday, 5:30pm

↑ Sources

-

From the Pari Center:

- David Bohm On Creativity; Excerpts delivered before the Architectural Assn, 8 Feb 1967

-

Dialogue - a Proposal,

Peter Garrett, David Bohm, Donald Factor- Why Dialogue?

- Purpose and Meaning

- What Dialogue is Not

- How to Start a Dialogue

-

David Bohm and Peter Garrett,

video transcript, 1 July 1990: - David Bohm 1917-1992, by F. David Peat

- David Bohm speaks about Wholeness and Fragmentation, 1990 (13:13)

-

Beyond Limits,

A Conversation with Professor David Bohm

by William M. Angelos, 1990, Film and Transcript

local film and mp3 (1:06:46) -

The Nature of Things with David Suzuki,

26 May 1979 (40:30) - John Cobb and David Bohm, 1984 (20:48)

- Changing Consciousness:

- The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory, D. Bohm & B.J. Hiley, New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Entering Bohm’s Holoflux: Explorations in Participatory Consciousness, Lee Nichol, Italy: PariPublishing. 2021.